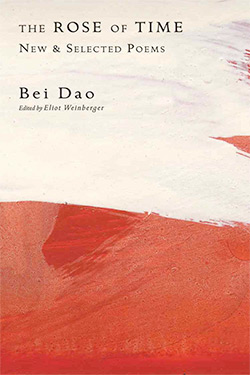

The Rose of Time: New and Selected Poems

by Bei Dao, edited by Eliot Weinberger

reviewed by Jonathan Hart

Bei Dao (Zhao Zhenkai) is a poet who was once a red guard during the Cultural Revolution in China and was then sent away from his native Beijing for re-education as a construction worker. He has lived in exile in the United States and western Europe and has spent time at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, where he teaches, and where there is an archive of his work donated by Bonnie S. McDougall. In The Rose of Time: New and Selected Poems, Eliot Weinberger brings together a bilingual edition of Bei Dao’s work, including translations of poems from 1972 to 2009 by McDougall, Weinberger, and others. Here, I want to speak about these translations as if they were poems in English on which the reputation of the poet stands in the English-speaking world. Despite the political engagement of Bei Dao, which is important, I want to concentrate on his lyric moments that may express a politics of obliquity.

The August Sleepwalker (1972–1986) includes “Untitled,” which begins with bold and unexpected imagery: “Stretch out your hands to me / don’t let the world blocked by my shoulder / disturb you any longer.” The poem uses the shoulder blocking out the world as an image of perception and barriers. This is a poem about not knowing, especially tomorrow, which “begins from another dawn / when we will be fast asleep.” How can we know when we are in a slumber?

In “On Tradition,” part of the same original book, the translation is crafted as a careful and concrete poem: the mountain goat standing on the precipice before a decrepit and arched bridge, asking a question about “who can make out the horizon / through years as dense as porcupines.” The image is a memorable personification: “windchimes / as somber / as tatooed men.” Day and night, they do not hear the ancestral voices, which are as the long stony night, but the poem ends with a twist: “the wish to move the stone / is a mountain range raising and falling in history books.” This landscape poem finishes with a vision, not explicitly assigned to people or a person, of a range of mountains, but not in nature, in a kind of time-lapse film of geological history, yet in a history book. This historical pattern is, in a Chinese setting, rise and fall, just as it had been in the medieval wheel of fortune, Shakespeare’s histories, and in Gibbon’s work on the Roman empire. Dao uses this politics of obliquity, which is no surprise in a culture given to central command and control.

“The Art of Poetry,” also in The August Sleepwalker, represents a speaker in a great house, with only a table in it, amid marshland without bound and a moon shining on him. The art of poetry is not addressed directly, and the moon shines “from different corners.” Once again, the images surprise: “the skeleton’s fragile dream still stands / in the distance, like an undismantled scaffold.” The question is how a skeleton can dream, and perhaps that is one reason it is fragile; the dream is a scaffold that is “undismantled,” a word that signals the shock of the strange. Again there is surprise with the image: “the fair-weather lightning that gleams in your palm / turns into firewood turns into ash.” Lightning in good weather is a kind of oxymoron, something pleasant and threatening, something that can shine in a hand and transform into wood and then to a kind of fire-dust. Poems from Old Snow (1991) continue in this vein. The title poem equates snow with a revival of an “ancient language” that changes national lands. The old and the new exist in contrast: “old snow comes constantly, new snow comes not at all.” The snow is part of a symbolic landscape in which “the art of creation is lost” where windows retreat, five magpies go past and sunlight is unexpected. The poem ends by yoking together nature and society in ways that bring together incongruous elements: “Green frogs start their hibernation / the postman’s strike drags on / no news of any kind.” There is nothing new, just winter, the same old thing, in snow and perhaps in politics.

“Reading History” is among the previously unpublished poetry and once more mixes images of nature and implicit politics. The poem begins with “hostile dew in an uprising of plum blossoms / guards the darkness etched by the noon sword / a revolution begins the following morning.” This is a poem of bitter widows, wolves on tundra, ancestors moving backward in prophecies, a river where the debates over faith and desire are furious and endless, a hermit and silent meditation, the sinking sun of kingship, the songs of flutes in a vacant valley. The poem ends with nature and culture in concrete images: “the seasons stand up in the ruins / fruits climb over the walls to chase tomorrow.” Natural time involves bearing fruit over a barrier to the future. Here is some hope in history.

The translators of Bei Dao have given us English poems of power in this collection that brings together his work over about three decades. Bei Dao’s poetry translates well in its bold imagery and implicit and oblique politics, using nature in a symbolism of indirection that is as subtle as it is apparent.

Published on March 18, 2013