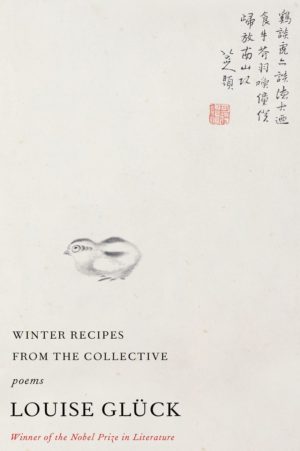

Winter Recipes from the Collective

by Louise Glück

reviewed by William Doreski

Louise Glück has always been an introspective poet, committed to probing difficult emotions. Her mode of self-objectification is one that few poets can effectively sustain. The Wild Iris, one of her most brilliant books, attributes complex emotions to flowers and to God. This enables her to speak through them with a candor that doesn’t work as well when her subjects are ordinary people. Averno builds on the classical descent to hell but situates that adventure in our own world. Framing her work with an ancient motif helps Glück achieve intimacy and engagement while maintaining an emotional distance free of sentimentality.

Winter Recipes from the Collective, her first book since winning the Nobel Prize last year, contains several longer poems that extend the dramatic mode of her previous collection, Faithful and Virtuous Night. Poems like “The Denial of Death 1. Travel Diary” feature dialogue, which allows them to express commonplaces and homilies the poet herself might avoid:

The concierge, I realized, had been standing beside me.

Do not be sad, he said. You have begun your own journey,

not into the world, like your friend’s, but into yourself and your memories.

As they fall away, perhaps you will attain

that enviable emptiness into which

all things flow, like the empty cup in the Daodejing—

While the concierge has accurately identified the means of some of these poems, he misunderstands their purpose. We are more likely to sense emptiness at the opening of a Glück poem than at its conclusion—although just what the poem fills us, and its speaker, with is not necessarily enlightening or comforting. In the Daoist parable, the empty cup is ready to be filled with something fresh and wise, while in Buddhist theology, emptiness is the blessed state of being free of desire altogether. In a characteristic Gluck poem, desire is already absent, and she has no interest in filling her cup with it. “I hate sex,” the speaker of “Mock Orange” (in The Triumph of Achilles) tells us, “the man’s mouth /sealing my mouth, the man’s / paralyzing body.” Desire is something we meet along the journey to hell, and it does not comfort, even if it sometimes illuminates.

The concierge, as we learn at the end of “The Story of the Passport,” is an avatar of the beloved. In Glück’s recent poetry this figure does not represent emotional stability or support. It is an abstraction that embodies itself in roles rather than in personhood. After the mid-career poems about her failed marriage, Glück rejects the autobiographical mode, avoiding any suggestion that the other exists outside the text.

Most of the poems in this new collection mull over emotional failures—not just the lack of desire or passion, but of basic human connections, as in “An Endless Story”:

Halfway through the sentence

she fell asleep. She had been telling

some sort of fable concerning

a young girl who wakens one morning

as a bird. So like life [ … ]

The struggle to connect but also to create, to tell a fable or an enlightening story, baffles the personae of these poems. This might seem like a negative poetics, but it enables the poet to link the creative self with the feeling self in a way that sidesteps problems of personality and to delve deeply into the muddle of perceptions and sensations from which poetry emerges. Asked by a blind art teacher, “what do you think of your own work,” the speaker of “The Setting Sun” replies, “Not enough night. [ … ] In the night I can see my own soul.” Night is Glück’s best moment. For others, night is a muddle of shadows, but for her the inability to see clearly fosters the cool introspection that shapes her work.

Aside from the complex emotional tenor of these poems, what makes them so readable is the narration—image succeeding image in a convincing flow of perception—and Glück’s agile free verse. It is easy to underestimate the difficulty of writing free verse. These poems offer a succession of short lines, long and short lines mingled, long line succeeding long line, unfolding with the inevitability that characterizes all good verse, metrical or free. Consider these lines from “Afternoons and Early Evenings”:

boutiques, restaurants, a little wine shop with a striped awning,

once a cat was sleeping in the doorway;

it was cool there, in the shadows, and I thought

I would like to sleep like that again, to have in my mind

not one thought. And later we would eat polo and saganaki,

the waiter cutting leaves of oregano into a sauce of oil—

Casual yet perfect, conversational yet inevitable, the verse fully formed yet informal, Glück at her best—and she often is at her best—is a master of lyric narrative. Although brief, this new collection offers some of her best work, especially the sequence poems “The Setting Sun,” “Winter Recipes from the Collective,” and “The Denial of Death.” Everyone seriously interested in poetry will be reading these for years to come.

Published on November 23, 2021