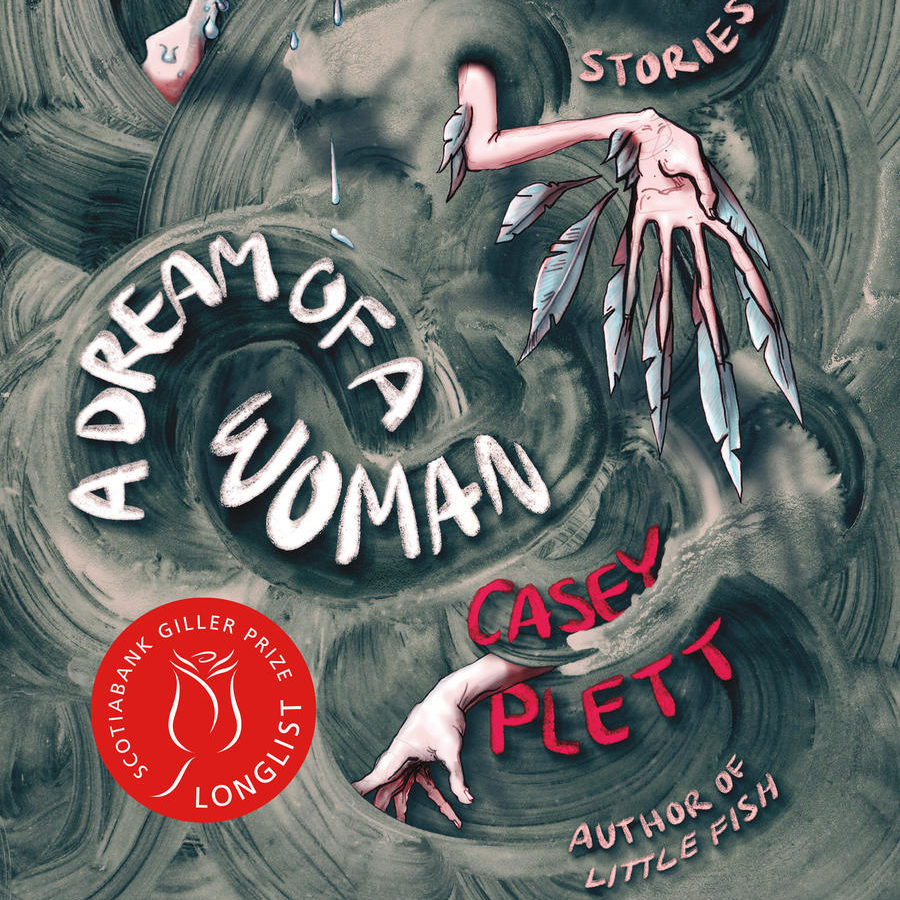

A Dream of a Woman by Casey Plett (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2021)

Contributor Bio

Casey Plett and Maria Marchinkoski

More Online by Casey Plett, Maria Marchinkoski

How to Write a Love Story: An Interview with Casey Plett

by Maria Marchinkoski

Casey Plett is a Canadian novelist whose 2014 short story collection, A Safe Girl to Love, and 2018 novel, Little Fish, each won a Lambda Literary Award. Her most recent short story collection, A Dream of a Woman, was longlisted for the Giller Prize. In a Zoom conversation, we discussed addiction, Mennonites, the mundanity of being trans, and the past and future of trans fiction.

Maria Marchinkoski: Early in your writing career, before moving to fiction, you wrote a column about your transition in McSweeney’s—

Casey Plett: Oh no.

MM: —which made me think me of the common expectation that trans women write only from their own experience. In both your short story collections and your novel, you write from the vantage points of so many different types of trans women—straight trans women, trans women in love with other trans women, sex workers, women who’ve had surgery and those who haven’t, women just beginning their medical transitions and those who’ve been transitioning for years. How has your relationship to memoir or writing autofiction changed over the years?

CP: When I started writing for McSweeney’s I was very young. I had just started transitioning and had not expected to get the job. Suddenly, I was like, “Oh shit, I have to write this column every two weeks.” But what drove me in the column was wanting to write from the perspective of a trans person who did not know they were trans from when they were three, or a trans woman who had always been attracted to women. I switched to fiction right afterward; I realized I had said what I wanted to say in nonfiction.

At that point in my life, around 2011 or 2010, I had read a bunch of trans memoirs and found them lacking. I wanted room for something weirder and younger and not from the perspective we had all seen before. This was before Janet Mock’s Redefining Realness blew everything open. It was before Nevada by Imogen Binnie, which did the same for fiction. When those came out back-to-back in 2013 and 2014, I realized I didn’t need to worry about where the gaps were.

MM: Trans lit has broken into a mainstream readership, into a general literary audience. Has that shift surprised you?

CP: It’s wild what has gone forward and what hasn’t. The fact that it took until 2021 for something like Detransition, Baby to come out is both surprising and not. It seems both like it never would have happened and like it took forever. It’s hard to predict what will succeed, and I think we sometimes do ourselves a disservice by trying to forward-engineer where trans literature will manifest in a larger literary world.

MM: Nevada became a model for trans fiction. It seems like it was a monumental change both for the genre and for you personally.

CP: On many levels. I realized I could talk about what I wanted to talk about and do what I hadn’t allowed myself to do. I felt freer as an artist and stopped trying to divine how my writing would be received. I would not have been able to write Little Fish had I not had that freedom in mind.

MM: There seems to be a cluster of recurrent concerns in A Safe Girl to Love, Little Fish, and finally, A Dream of a Woman—involving sex work, trans women from Mennonite families, and alcohol addiction. How have you built on these themes through your work?

CP: I never thought the two worlds of Mennonites and trans people could interact. They seemed incompatible, both in my life and in writing. Fiction has surprised me that way. That said, I think fiction writers have an attraction to writing about certain things and not others. For example, I come from a Mennonite background, so of course I’m interested in writing about it. But I was also a theater kid in high school and I’ve never written about that.

You can’t talk about trans history or trans communities without talking about sex work. There’s also a long history of trans women and addiction. Many trans people have problems with amphetamines or opiates, but I mostly write about booze. I try to keep a certain degree of alchemy and mystery in why I write about certain things and not others. I can already feel myself getting interested in some other things that haven’t shown up in the first three books.

MM: Your writing seems to challenge many of the formulaic narrative expectations of being trans. For example, a character might change pronouns or change their name very quietly in a story. Do you try to take a similar approach when writing about addiction? I imagine there are similar narrative expectations that a general reader who isn’t in those worlds might have.

CP: It’s occurred to me that addiction has come into play in the ways that I’ve untangled toxic narratives about transness for myself. Pretty much every portrait of addiction I’ve seen in a long-form narrative ends where the person either doesn’t get better and dies, or gets clean. But every day addicts wake up and do not have either of those experiences. That does mirror how I feel about transness, in that there are these uncomplicated narratives that don’t translate to how things manifest in daily life. I felt interested in the mundane ways that addiction can express itself. Sure, there is destruction there, and sure, there is trauma, but there’s also a lot of mundanity. Maybe in a similar fashion, I’m interested in the mundanity of transness and in the mundane ways that transness affects trans peoples’ lives.

MM: The winter in Winnipeg is so integral to the tone of Little Fish, and then you have stories like “Enough Trouble,” set in an unnamed small town, where the atmosphere of a place matters more than the specificity. How do you go about determining setting?

CP: I’m someone who’s moved around, and I’ve had the good fortune to travel a lot, mostly around the United States and Canada. Walking around a new place or in different weather can feel like living a different kind of life. Many artists already understand that, and yet I find myself so bored when I read someone tripping over themselves trying to sound local.

Before writing setting, I try to figure out what’s important about its atmosphere. With Little Fish, it was easy. One of the starkest experiences of my life has been winter in a city in the Canadian prairies, specifically if you don’t own a car and don’t have a lot of money. That is an extremely specific experience, one where your body enters a different state of being. You can go months without seeing grass and months without the temperature getting close to above freezing. I try to be conscious of the actual bodily experience of a place. What does it feel like when you wake up and have to run an errand, and then something sidelines you, and you have to take care of it before you get home? That’s what I’m interested in.

MM: I think it’s fair to say that love stories, however complicated, play a pretty big role in your writing. What does it take to write a love story and how has that changed for you over the years?

CP: I think the answer there is specificity and energy. So, for example, with the character of Nicole in “Rose City, City of Roses,” it became her reflections on these two women from her past—one, Sue, who is dead and to whom she was never romantically attracted, and the other, Cleo, who is very much alive and once made a pass at her. She’s so lonely and doesn’t want to be lonely anymore, but she also knows she’s not attracted to Cleo. Those felt like the specific ways in which this person is experiencing this emotion, and I think that about some of my favorite love stories. So, for example, I love Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

MM: Which appears in the first story of A Safe Girl to Love.

CP: Good catch! There are a million reasons why that movie is brilliant but part of it is that you believe in the characters’ ability to attract and repel each other. You can do whatever you want in a love story so long as that energy exists. If I don’t believe that two people relate to each other, everything else can be the same and it will still be boring. To me that has to be the core of any love story: do I really believe this is how these two people feel about each other and how they will act around each other? Sometimes it’s not what we want it to be. Sometimes as a writer it’s not even what you plan for. When I first started writing “Hazel & Christopher,” I’d written the first half and I couldn’t figure out why I couldn’t finish it. Eventually I realized that it had to do with what happens with Christopher at the end of that story. It was an ending I had tried to avoid; it seemed impossible. I waited on that story for years and finally realized that I just didn’t want to admit it.

MM: Speaking of complicated love stories, the novella “Obsolution” (from A Dream of a Woman) looks like a one-off short story, but it recurs intermittently throughout the book, telling the story of Vera’s transition and her evolving, troubled relationship with a cis woman, Iris. Why did you decide to split it up over the course of the collection?

CP: I wrote just a short story initially. I had the first chapter and something like an ending. Then, after the first chapter, I realized there might be more to talk about. I was interested in two things: it was the first time I’d written a “transition story” in fiction from the beginning; and it was also a vehicle to talk about this weird, complicated relationship. Initially I split the story because it felt right. The sections felt like chapters, like they weren’t meant to be read all at once. As I kept working on the collection, the effect of what I was trying to do became stronger. The story is about memory, forgetting, and forgiveness in ways that aren’t linear and clean. In some of the last conversations she has with Iris, Vera claims not to remember things that we’ve already read for ourselves.

MM: And we have to re-encounter it too because we’ve read other stories in between.

CP: Exactly! If it was all together you would think, “Oh yes, I remember now,” like when the last twenty minutes of a movie harks back to the first twenty minutes. Hopefully the separation mimics the effect of how actual memory works. And who’s to say whether Vera has a good handle on things?

MM: What writers do you read now that you wish had more recognition?

CP: I think that anybody who has not picked up Summer Fun by Jeanne Thornton is missing out. That book is brilliant and hilarious and sad. This is mostly a shoutout to people who do not have a relationship to Canadian literature: I’m reading Katherena Vermette’s The Strangers right now. She’s one of the best writers I’ve ever read. If you haven’t read her book The Break, you’re doing yourself a disservice. If you have, then get hold of The Strangers. In terms of trans lit that I think maybe doesn’t get enough recognition, Calvin Gimpelevich’s Invasions is still one of my favorite books of short stories. Score a copy if you haven’t.

Casey Plett’s latest book is the story collection A Dream of a Woman.

Published on May 5, 2022