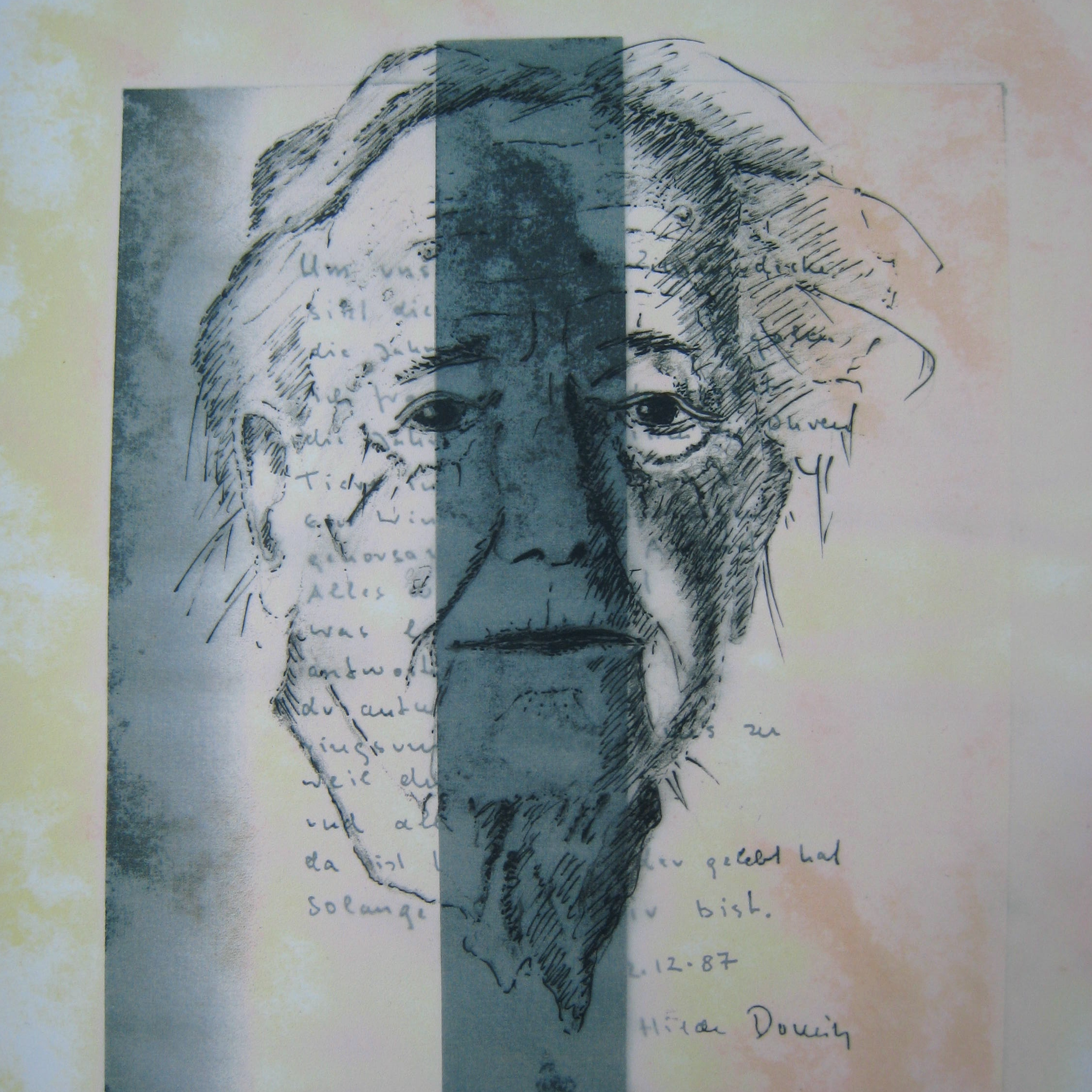

Shadow and Radiance: The Poetry of Hilde Domin

by Peter Brown

At last, the poetry of Hilde Domin, one of Germany’s finest twentieth-century lyric poets, is available in English. Two selections were published this April: With My Shadow, translated by Sarah Kafatou (Paul Dry Books), and The Wandering Radiance, Selected Poems of Hilde Domin, translated by Mark S. Burrows (Green Linden Press).

Born Hildegard Löwenstein in Cologne in 1909, the poet adopted the pseudonym Domin in gratitude to the Dominican Republic for accepting her and her husband as refugees in 1940. Their return to Germany in 1954 and Domin’s dedication to writing in German, the language of her childhood, are elemental aspects of her poetry and provoke many fundamental questions. What would a beautiful poem be, for example, for a Jewish poet who returned to Germany and wrote in German so soon after World War II? Domin introduces the problem in the poem “Schöner” or “More Beautiful” (Burrows’s translation):

The poems of happiness are more beautiful.

Just as the blossom is more beautiful than the stem

that propels it

poems of happiness are more beautiful.Just as the bird is more beautiful than the egg

as it’s beautiful when light comes

happiness is more beautiful still.And more beautiful still are the poems

I will not write.

There are many beautiful poems in these books, both in English and German, but the poet’s insistence on lyrical precision and moral clarity in combination with an intentional elusiveness—her “unspecific exactness”—often casts doubt on some of the stances she adopts elsewhere in her writing. She rarely allows herself a resting place, at times risking sentimentality, but then quickly subverting complacency, as in “Warnung” (“Warning”):

When the small white streets

in the south

where you once walked

open themselves to you like buds

full of the sun

and invite you.When the world,

fresh-skinned,

calls you from your house

and sends a unicorn,

saddled,

to your door.Then you should kneel down like a child

at the foot of your bed

and pray for humility.

When everything invites you,

that’s the hour

when everything deserts you.

Disappointment, surrender, and fear infiltrate memories of a cherished childhood. Even humility provides little comfort:

Humility is like a well.

One falls and falls

into the bottomless shaft

and the cost of solace

steadily rises.

Kafatou’s selections follow the order presented in the collected poems, Sämtliche Gedichte, published by S. Fischer Verlag in 2009. The first poem serves as a kind of prism through which we glimpse the colors and tones of Domin’s lifelong project: the tension between flight (weightlessness) and solidity, the “play of light and shade,” the complexities of what it means to have once had a home, the courage required of an expelled Jew who reclaims Germany and its language, as well as the enduring political and cultural fact of Germany itself—“the grave of our mother”—as in “Ziehende Landschaft” or “Moving Landscape” (translation by Kafatou):

One must be able to depart

and yet be like a tree:

roots firm in the ground,

as if the landscape were leaving while we stand still.

One must hold one’s breath

until the wind dies down

and unfamiliar air starts to flow around us,

and the play of light and shade,

of green and blue,

displays the old pattern,

and we are at home,

wherever that may be,

and can sit down and lean

as if on the grave

of our mother.

When Hannah Arendt was asked what she missed about living in Europe, her answer was “die Sprache,” that is, German, her mother tongue. Like Domin, Arendt came from a comfortable, educated, secular family. Both report being raised with dignity and confidence in a culturally enriching environment, their childhoods providing a deep and favorable sense of who they were. For Domin, German is the language of belonging and intimacy, what she calls the “last irrevocable home,” where it’s possible to do what most great modern poems do: create the illusion of intimacy between the voice in the poems and their reader. Her poems address us in their “small voice,” like a mother whispering to a grieving child, or a child to her mother:

I count the raindrops on the branches,

they gleam, but don’t fall,

shimmering strings of drops

in the bare branches.

The meadow looks at me

with large eyes of water.

Solace is nowhere in the enchanting imagery; there is often no place to stand:

Restless brilliance, blade

swung in a wide arc,

sickle of sun.I lie there like the meadow

and feel your knife,

mower,

irresistible and cold,

moving closer.And all the flowers

panic

in my heart.

The wonder of these translations, both Kafatou’s and Burrows’s, is how the poems whisper to us in English as well. It’s a mysterious effect, accomplished not only through close attention to sense—that “play of light and shade,” of clarity and elusiveness—but to the sounds of speech, where the poet-translators’ arrangements form a kind of language within the language. I often want to listen only to the music:

My shadow

the smallest loneliest

among the deadOn the island of light

straying

masterless

Both translators’ introductions are authoritative and informative. They celebrate Domin’s optimism, though Kafatou’s commentary is more circumspect, as if to make sure the poems speak for themselves. The light that permeates so many of the poems receives a different emphasis, even a spiritual intensity, in Burrows’s book, which, with its cover awash in bright, warm greens and yellows, could almost be mistaken for a guide to religious affirmation rather than a book of complex, darkly modern poems.

More emphasis is given, in Burrows’s selection, and in the foreword by Marion Tauschwitz, to the centrality of Domin’s determination to “love nevertheless” despite the shadow of the war and her painful marriage. The poems in this selection more frequently reveal Christian forms—a celebration of Christmas, an invocation of the saints, a crucifixion—and a whiff of controversy arises from a portion of Tauschwitz’s foreword in which she describes the reaction to Domin’s first book, Nur Eine Rose als Stütze (Only a Rose for Support):

[Domin’s] return to Germany … was an experience of utmost fragility. To exchange the feeling of return for the feeling of being-at-home called for fresh courage: the courage of forgiveness. … When the philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer subsequently called her the “poet of return,” this was balm for those German souls who saw her, as a Jewish-born poet, as one who after her return was prepared to forgive and thus purportedly mitigate their German guilt. Jewish colleagues, and above all the poet Paul Celan, held this against her. The initial euphoria over her first book of poems was followed by years of struggle against the male-dominated literary scene of the times.

Tauschwitz’s abrupt pivot away from Celan’s resentment and the fraught notion of forgiveness to the too-easy target of male dominance in the postwar literary scene raises many questions. What does Tauschwitz mean by “Jewish-born” poet? Was Domin only Jewish by birth? Did she at some point no longer consider herself a Jew? Was it only Celan’s “Jewish colleagues” who were troubled by this supposed inclination toward forgiveness? What could forgiveness of Nazi Germany by an individual poet even mean in this historical context?

Kafatou points out that Domin’s poems seek to speak “to the moral core in each person,” and the poems in both books explore endurance, remembrance, responsibility, belonging, tolerance, a love for what is “unlosable,” and a determination to love “nonetheless.” While Burrows’s translations often seem to strive for philosophical exactitude, Kafatou’s prioritize concision and musicality, though it would be a mistake to overstate this comparison. And, if I have quibbles with the translations here and there, what matters is that these translators and publishers have made an important contribution, bringing us two books that deserve widespread attention.

Published on November 21, 2023