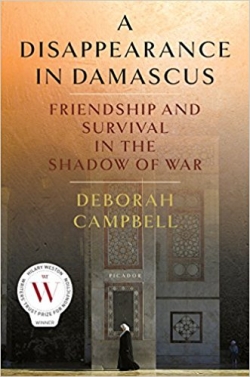

A Disappearance in Damascus: Friendship and Survival in the Shadow of War

by Deborah Campbell

reviewed by Ophelia John

A Disappearance in Damascus, the second book from Canadian cultural immersion journalist Deborah Campbell, swept Canada’s nonfiction prizes in 2016, garnering the Hilary Weston Prize, the Hubert Evans Prize, and the Freedom to Read Award. Coming fourteen years after the publication of her first book, This HEATED Place: Encounters in the Promised Land (2002), and following many years of journalism in the Middle East, Disappearance combines deep research with sharp, keen prose.

My own interest in Deborah Campbell’s work dates to 2011, when I was a student in her online creative nonfiction class at the University of British Columbia. During that eight-month course, along with workshopping our profiles, memoirs, and pieces of literary journalism, Campbell also gave candid advice. When it came to choices like creating composite characters or bending timelines in nonfiction, we each had to answer to our own gods, she said. For a conflict journalist, the repercussions are too grave to take narrative liberties. As she outlines in Disappearance,

When states attack journalists it is typically when they think they can get away with it, which is why they usually focus on their own citizens or on journalists from countries with weaker governments that can’t or won’t do anything to protect them. The major risk is to your sources—the people who talk to you and help you and face the consequences long after your story has run and you are gone. Especially to your primary source, your fixer.

Those potential consequences came to life when, over the course of researching an article on Iraqi war refugees in Syria for Harper’s, the restrained, wary Campbell and her fixer, a warm, charismatic Iraqi refugee named Ahlam, became friends. A person with her own way of navigating the fault lines of her society, who “saw what needed doing and did it,” Ahlam is as fearless in Damascus as she was in Iraq, where she had already survived one kidnapping. She organizes a school for girls and helps others whenever she can.

The two women share some fundamental qualities: “Both of us had grown up in communities that told us who we were going to be and had managed to rebel. … We had both made it out through education. She had the help of her father against the barrier of culture; I had the help of my schooling against the barrier of my father.”

But in Damascus, Ahlam’s role as a community activist earns her the mistrust of the authorities. Disappearance chronicles her arrest (which Campbell witnesses) and detention by Syrian secret police, and how Campbell tries to help her friend while running the dangers of police attention herself.

Interestingly, Ahlam’s arrest takes place more than halfway through the book, in what screenwriters would call a “mid-point turn,” rather than the event being used to set the story in motion. Within this challenging structure, Campbell keeps the story taut and the reader focused for nearly two hundred pages while she sets the stage, explains the players and the deep complexities of the Iraq war, and hints at what’s to come. When Ahlam disappears into the maw of state security, the narrative becomes as tense as a garotte.

One of the texts that Campbell recommended to our class was Janet Malcolm’s The Journalist and the Murderer, a coldly perfect book in which Malcolm does not shy away from self-interrogation. Campbell takes Malcolm’s approach further: she believes that she may be the cause of Ahlam’s kidnapping.

“They are saying you are Mossad or CIA,” he [a Syrian journalist] continued, without clarifying. “That’s why she was taken.”… He told me I had to move out of Little Baghdad. Now. Today. Immediately.

Trying to locate Ahlam and obtain her release without making matters worse, Campbell amplifies all of her usual cautionary habits. But it becomes increasingly difficult to distinguish between paranoia and the evidence of surveillance, and as her own psychological state deteriorates, she leaves Damascus for Beirut to seek advice from an old friend, nightclub owner “Emperor Michel I of Nowheristan.” The kind of secondary character who could easily hijack a novel, the Emperor is a man with his finger on the pulse, whose “drug of choice was information.”

Armed with the Emperor’s counsel, Campbell returns to Damascus, where Hamid, another fixer, consents to meet with her again despite having been warned off by the authorities. The generosity of these few brave people is one of the book’s throughlines. Campbell lays Hamid’s essential character open in two sentences: “Meeting me now placed him in danger. I knew he only did so because loyalty was built into his marrow, a quality even self-preservation could not trump.” And Campbell, the detached journalist, comes to understand a truth that had previously escaped her:

Now that my belief in freedom of action, in agency, was gone, it seemed to me that it must have been an illusion all along. … In the West we are taught this from birth: that the course of our life is determined by how well we play our cards. … Only now was I coming to understand the sense of fatalism so common in the East, where most of what happens is determined by forces beyond one’s control.

The book is stellar for many reasons—the minute characterization, the narrative tension, the deft summary connecting the Iraq and Syrian wars. Arguably, certain lighter anecdotes—a trip to a hammam, buying a blue shirt and dress—could have been left out to no ill effect. But inducing readers jaded from decades of war reporting to pay attention to the fate of one single female Iraqi refugee is not easy; Campbell describes the role of the war journalist as that of a “go-between” (as per L. P. Hartley’s famous title). To write a story from a world apart is one thing; to have a reader feel that story is another.

And here’s where Campbell is a true go-between. A private person (her self-described “now-chronic reticence” rings true), as a writer she is willing to offer up pieces of herself in order to bridge the sociocultural distance between the reader and the characters. Against the backdrop of a Damascus cityscape both graceful and harsh, Campbell slowly reveals her faltering long-distance relationship and moments from her childhood that link to episodes in Ahlam’s. In the process, the veils separating the readers from the characters lift—and the person left standing in front of our eyes is not Deborah Campbell, but Ahlam.

Wisely, Campbell continues Ahlam’s narrative past the usual third act, for this is a story that doesn’t have a conclusion, just as no war truly ends with a peace treaty or liberation. As an American ex-military man tells Campbell during her flight out, “This. Will. Never. End.”

Published on December 18, 2017