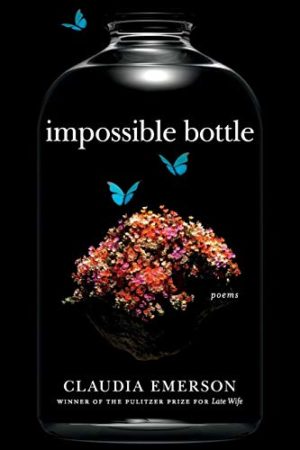

Impossible Bottle

by Claudia Emerson

reviewed by Julie Swarstad Johnson

When Claudia Emerson describes a woman who paints with the materials available to her—shoe polish and worn-out shirts—she also describes what she accomplishes in Impossible Bottle:

[…] her face the glass

she had to look through,and what she could see of the world she saw

through it, indivisiblefrom the back pasture

(“Kiwi”)

Impossible Bottle, published after Emerson’s death from cancer in 2014, refracts a dying speaker’s inner life through her intently observed surroundings, distilling this view into masterful loose iambic verse. “[A]ll of it she cast again and again / in what she had to,” Emerson writes about the shoe-polish painter. This same urgency vitalizes Impossible Bottle: written and completed in the last months of the Pulitzer Prize-winning writer’s life, these poems capture Emerson urgently coming to poetry to say what she must say.

Emerson’s six collections have explored the cycles of life set against the geographical and cultural landscapes of the American South. She has consistently done this in a blank verse identifiable as such but also perfectly elastic, shaped around the rhythms of contemporary speech. “The trees redden beneath it, before loss,” Emerson writes in “Infusion Suite,” the world “becoming livid,” “the light, the sky a low // opalescence” (No. 6). However Emerson’s lines scan, blank verse provides a scaffold just beneath the surface, something rested upon but also pushed against. In Impossible Bottle, echoes of Emily Dickinson reverberate in a repeated structure: couplets of loose iambic pentameter and trimeter read like a variation on Dickinson’s ballad stanzas. A suite of poems titled “Metastasis” fits within the tradition of Dickinson’s fragmented, ecstatic visions:

outside at home a voiceless God

flames there late beesa burn slow miraculous such green there

there you are

(“Metastasis: Intercession”)

The astonishing world catches our attention through slant rhyme and assonance or alliteration, exact or just off. A moth’s damage is “fragile lace-like // the constellate erasures of the coat / it makes for you to wear” (“Metastasis: Worry-Moth”) while “your brain” becomes “the bewildered margin / of this city,” an owl’s “sight poor majestically / so as yours” (“Metastasis: Owl”). The “Metastasis”—a word to incite the deepest dread—poems notice cancer-like destruction in the world, and, miraculously, they record it as beauty. English ivy run amok on trees can be described as both “a blight / of sleeves” and “full and green” (“Metastasis: English Ivy”). The speaker of these poems confronts decay but revels in the flame of bees, in moths’ delicate erasures.

Death recurs frequently in all of Emerson’s work, a reflection of a life riddled with the repeated losses of family and friends. The poems in Impossible Bottle, however, move towards transcendence. “Chain Chain Chain” begins with a litany of the many who have died from among the speaker’s wedding party, but ends with the speaker burning her exquisitely embroidered Mexican wedding dress in a fire described as—strangely, liberatingly—“set / for this.” Images of death from Emerson’s earlier work also return in altered form. “Ground Truth,” from Secure the Shadow (2012), contains a dangerous storm on the day of a funeral that dissipates into “winds // diminishing, the light, afternoon’s concession / to another dusk—severe, more common truth.” A superstorm appears here in “Weather,” a poem dedicated to Emerson’s husband, in which the speaker’s beloved responds to the danger by

[…] leaning into it,

almost as though to dare it,test it, touch the hem of it, or let it

touch you; before you knew,you knew it would spare us.

Coming after preparations with “batteries, candles, canned fruit,” Emerson concludes with the beloved choosing to confront enormity.

These poems, and Emerson’s poetry at large, merit attention for their vitality in image and sound. Through careful attention to place, the rhythms of speech, and the patterns of a life, Emerson’s poems achieve a living form on the page. Her career as a poet has been built on this accomplishment, and in Impossible Bottle she attains otherworldly clarity. The speaker of the final poem describes her mother as a child waking up from a faint to find

[…] her mother seeing her

the way she sees me through this indelible

sill of ash—and behind it the fire that had given the stove-eye

its brightest-ever aura.

(“The Scar”)

Impossible Bottle recognizes the indelible distance of death. Emerson sees an exhausted man in a hospital waiting room and says, “I will not mistake his / loosely sleeved sleep for anything else” (“Infusion Suite” No. 11). And yet, Emerson’s poems see beyond our present “sill of ash” to the wild beauty of the fire, leaving us at last with that “brightest-ever” gift of heat and light. May Emerson’s poems impart such gifts to readers many lifetimes over.

Published on February 1, 2016