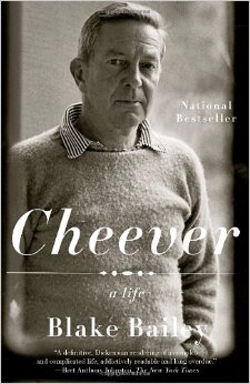

Cheever: A Life

by Blake Bailey

reviewed by Michael Shinagel

Blake Bailey made a notable appearance on the literary scene in 2003 with his acclaimed biography of Richard Yates, A Tragic Honesty, an event that created a revival of interest in the neglected writer, including a movie version of his best novel Revolutionary Road (1961).

In preparation for writing this biography of the life and works of John Cheever, Bailey consulted the major archives of Cheever holdings, read all 4,300 manuscript pages of Cheever’s journal, interviewed scores of family members and friends, edited the two-volume Complete Novels and Collected Stories and Other Writings for the Library of America, and collected photographs and reminiscences from every conceivable source. This exhaustive research is evident in the finished work of 770 pages, arranged chronologically into fifty chapters, including thirty-two pages of photographs and a detailed index.

As Bailey demonstrates dramatically, Cheever’s writings and his life are intertwined like a double helix. His dysfunctional family life in Quincy, Massachusetts, scarred him emotionally, but the high school dropout had his first taste of literary success at the age of eighteen when his short story “Expelled from Prep School” was accepted by Malcolm Cowley of the New Republic. He would have to wait until he was twenty-two before The New Yorker bought the story “Buffalo,” but by the end of his life he had had a total of 121 stories published in the magazine. His success as a short story writer, however, left him unfulfilled; he knew that he needed to write novels to establish his reputation.

In 1941 Cheever married Mary Winternitz and they had three children: Susan, Benjamin, and Federico. For most of his life Cheever would experience money problems and he periodically had thoughts of suicide. In 1952 he finally completed his first novel, The Wapshot Chronicle, which won the National Book Award. While his writing received critical acclaim, in his personal life Cheever suffered from alcoholism, depression, sexual frustration, and family strife.

Bailey has clearly mined Cheever’s personal journals and other sources for intimate knowledge of his bisexuality, his strained relations with his children, his prodigious drinking problem, his precarious finances, his marital discord, his male and female lovers, his travels abroad, and his relations with contemporary writers, such as Irwin Shaw, John Updike, John O’Hara, J. D. Salinger, Ralph Ellison, Norman Mailer, Philip Roth, Bernard Malamud, and especially Saul Bellow.

Bailey traces Cheever’s literary career in detail, commenting insightfully on his stories and novels, as well as his many awards and honors, including his Guggenheim fellowships, honorary degrees, appearance on the cover of Time, and election to the National Institute of Arts and Letters. At the end of his career, after he nearly died of alcoholism and finally gave up drinking, he saw The Stories of John Cheever (1978) become a best-seller and win the Pulitzer Prize.

Each of Cheever’s seven short story collections, from The Way Some People Live to The Stories of John Cheever, as well as all the novels, from The Wapshot Chronicle to his last works Falconer and Oh What a Paradise It Seems, are discussed knowledgeably and incisively by Bailey, who must be lauded for his comprehensive treatment of Cheever’s life and works. Bailey has written the definitive life of John Cheever, a monumental accomplishment that honors the author’s literary achievements while also depicting graphically his tormented personal life.

Shortly before his death from cancer in the spring of 1982, a frail Cheever stood on the stage at Carnegie Hall to receive the National Medal for Literature. In his acceptance speech, he declared that “A page of good prose remains invincible.” A writer’s writer, the American Chekhov of suburbia, Cheever never compromised his literary credo. It remains to be seen if Bailey’s biography can spark a revival of interest in Cheever as he did for Yates.

Published on March 2, 2015