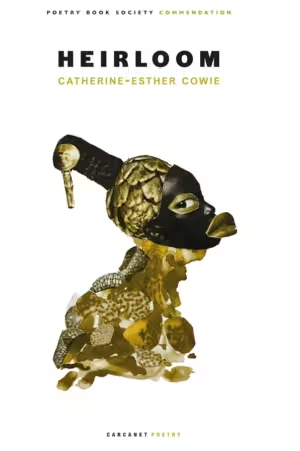

Heirloom

by Catherine-Esther Cowie

reviewed by Rhony Bhopla

Heirloom, the debut collection of poems by Catherine-Esther Cowie, is a haunting and courageous look back into the history of family, origin, and disappearing languages. It serves as a reverberant reminder of the impact of colonialism on the island of St. Lucia. The poetry collection has been awarded a Poetry Book Society Commendation.

Wasn’t I a servant to them too? Their

…………stifled sounds pressed

into the letters I gifted, they begot

a bastard tongue,

…………a burst. Shout. Long song.

This implicating erotesis is from the poem “Origin Begs for Hymns” in the section Prelude. Of the book’s five sections, four are named after women whose narratives inhabit the stillness of the page with visceral language. The collection is a devastating story of domestic abuse, where past generations of women come to life as Cowie creates monologues in their voices. The book is woven into the larger history of the St. Lucian struggle for freedom from the patriarchal grip of colonialism.

Cowie uses subtitles to signify events in St. Lucia, such as “My Englishman St. Lucia, 1942,” “Early Morning Rescue Castries, 1951,” and “Catherine St. Lucia, 1848.” This stamp upon the poems draws parallels between interiority and a larger state of affairs. Each poem invites the reader to traverse boundaries of language, narrative, and what has yet to be learned about the imposition of coloniality.

The poems range from single stanzas, staggered lines, couplets, quatrains, and monostiches. In “Reasons to Hit a Child,” content and form connect power, violence, victimhood, and the cycle of perpetuation.

Because the sun grows in her left eye.

Because a misfired belt buckle.

Because her skin hasn’t turned, and

Because the neighbours gossip that a white man

sleeps under your bed.

Because if you spare the rod, you spoil the child.

Because the porridge-sticky pan still sits on the stove.

Because her mouth is so full of your name,

Mama, Mama, Mama …

Because as a child, you snapped branches in two,

kept time to a hand slapping your mother’s face.

Because rage has its own flight.

Because there is pleasure in pinching flesh

until it flashes red.

Anaphora draws us through each subsequent monostich as a new moment unravels. This piece is nuanced with its ability to shift perspective, such as in the fourth line: “that a white man / sleeps under your bed.” Here we discover that the poem addresses the mother. Answering the title’s provocation creates momentum. Yet, a couplet toward the end reports a stark truth: the mother kept time while her own mother was being slapped. The couplet in its plainness functions to tie events and generations together.

St. Lucia is where Creole (Kwéyòl) is spoken, which, like many languages, is slowly disappearing from use because of the ravage of cultural erasure by the colonial empire. Nevertheless, Cowie expresses a lasting wonder about the island. Birds such as warblers and finches, which are endangered, are mentioned in a poem. In “The War St. Lucia, 194⏤,” alliteration, consonance, and rhymes add dimension to a description of the island: “But still it’s Sunday, the trees shake / like shac-shacs in the breeze, / and the sea goes on and on / with its lullaby like it has never / given cover to the enemy.”

Heirloom is a work of feminist significance and artistic beauty. Catherine-Esther Cowie has brought forward women who were silenced in their pain, and the collection is an extraordinary example of how poetry informs the record of history and its impact on humanity.

Published on January 5, 2026