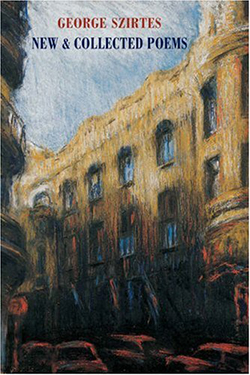

New & Collected Poems

by George Szirtes

reviewed by Carmen Bugan

On November 4, 1956, the Soviet army invaded Hungary, crushing the national uprising led by Prime Minister Imre Nagy. The attack on Budapest was devastating, with tens of thousands killed and many more seeking political asylum to the West. Among them was the family of the poet George Szirtes, then eight years old. Alongside family memories of the Holocaust, this experience of exile is the background against which his work must be read.

The repercussions of this moment can be traced throughout Szirtes’s poetry: from the early decision to address his father with the casual “You” to the moving series of sonnets “Portrait of My Father in an English Landscape” and the memory of himself and his father in Budapest in “Eclogue: Fair Day,” where the instant of two lives doesn’t, at least on first reading, seem to matter at all in the broader picture:

Fair day in Budapest, now tucked into history

In the way you slip a bus-ticket into a book

Or it may be a postcard, or a strip from a serviette

In any case temporary and sure to fall out

When the volume is opened, as it has been, and often.

It is, after all, only a child and his felt-hatted father.

What falls out of history, and is, despite everything, retrieved in order to hold the place where “reading” was interrupted, is a primordial moment, long lost, found again and folded into the larger story of our common past. There is a similar moment in Czeslaw Miłosz’s poem cycle “The World,” where the poet also first learns about his surroundings with his father. But exile means that child and father will never grow old together walking in Budapest, and the language in which their story is written will never be Hungarian. It is fortunate that Szirtes’s New & Collected Poems appears on the eve of the twenty-year anniversary of the end of communism in Europe because his poems are as important for their historical provenance as for their artistic excellence.

George Szirtes is now sixty years old. He can be claimed by the English as their poet, for he has been living and writing here for most of his life, saying, “I’m being bedded in— / to what kind of soil remains a mystery, / but I sense it in my marrow like a thin / drift of salt blown off the strand. I am / an Englishman, wanting England to win” (“Preston North End”). He can be claimed by Hungarians, for many of his metaphors originate in memories of his homeland and he is an active translator from his native language. And he can be claimed with equal right by exiles, for his poetry is founded on the crossroads between cultures and languages. In short, this volume expresses a significant part of the contemporary European consciousness through the unmistakable voice of one man.

In his memoir Speak, Memory, Vladimir Nabokov evokes in lyrical English a childhood sleigh ride remembered while walking in a snowy forest in Vermont: “The vibration in my ear is no longer their receding bells, but only my old blood singing. All is still, spellbound, enthralled by the moon, fancy’s rear-vision mirror. The snow is real, though, and as I bend to it and scoop up a handful, sixty years crumble to glittering frost-dust between my fingers.” Suddenly the Vermont snow has something Russian in it, just as American literature now contains Nabokov’s unique language. Much of Szirtes’s poetry has a similar effect. It is also the “old blood singing,” from the first collections that experiment with form and expose the clutter of life, to the books from Portrait of My Father in an English Landscape onwards that weave music, image, and memory into complex and pellucid verse.

Szirtes’s tone can be ironic and humorous, or confessional and serious, while always beckoning the reader to listen. He masters the poetic forms and the English language, writing often about language and its adequacy. In “Book,” the printed text is nothing more and nothing less than human flesh: “The books lie open like a pair of lungs / Breathing words.” The poem continues:

This is a story. Tell me another, until

The stories are exhausted and the dead

Retire to their grave bedrooms in a hill.

Here we have a comforting vision of the world, where graves are really only bedrooms in the hill, where stories are being spun and spun again, and where the living and the dead coexist, for better or for worse. Here is the old blood singing.

Published on June 21, 2013