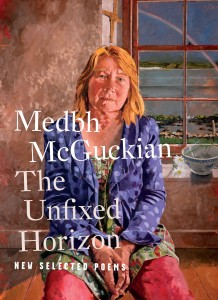

The Unfixed Horizon: New Selected Poems

by Medbh McGuckian

reviewed by Heather Clark

Medbh McGuckian is widely regarded as one of Northern Ireland’s foremost poets, though this was not always the case. After she won her first major British poetry prize in 1979, the committee tried to rescind half of the thousand-pound award when they learned that she was a pregnant Belfast schoolteacher. The controversy confirmed her sense that “being a woman for me for a long time was being less, being excluded, being somehow cheap, being inferior, being sub,” as she told an interviewer in 1998. Yet the publicity helped her secure a contract for her first book, The Flower Master and Other Poems, in 1982. Since then, McGuckian has attempted to disorient our poetic sensibility through her dense, circular verse. “Our normal language is not very thick with new thoughts,” she has said. The Unfixed Horizon: New Selected Poems shows McGuckian’s best attempts to invent “new thoughts” through radical juxtapositions that, in her words, “startle the senses out of their apathy.”

The poems in this selection, chosen by two scholars rather than McGuckian herself, are at once lyrical and abstract, intimate and oblique. “I prefer the winding intricacy of complicated narratives that don’t spell things out,” she has said. Yet the intimacy of McGuckian’s poems is illusory; the associations and images are so personal, so private, that they dislocate the reader in space and time. We lose our bearings, which seems to be the point. The beginning of “No Streets, No Numbers” from Marconi’s Cottage (1991) is typical of her “winding” style:

The wind bruises the curtains’ jay-blue stripes

like an unsold fruit or a child who writes

its first word. The rain tonight in my hair

runs a firm, unmuscular hand over something

sand-ribbed and troubled, a desolation

that could erase all memory of warmth

from the patch of vegetation where torchlight

has fallen.

Not all McGuckian poems are so opaque. Her elegies for her mother, such as the poignant “She Is in the Past, She Has this Grace,” are more direct. Yet most of McGuckian’s work, which is often set within domestic interiors, is written in syntax that attempts to “undo” or “unwrite” language itself. This tendency has led some critics to align her with écriture féminine, while others praise her “resilient ambiguity” and “dynamic tension.”

McGuckian’s disjunctions have also met with critical skepticism. In 1984, the Northern Irish poet James Simmons suggested McGuckian was deliberately writing “alluring nonsense” to mock the excesses of literary reviewers. The American poet David Mason accused her of “sheer pretentiousness” in 2000. It was only after she published Captain Lavender (1994) and Shemalier (1995), which dealt more explicitly with the Troubles in Northern Ireland, that accusations of political disengagement were put to rest. Some selections from those volumes, such as “The Albert Chain” and “The Feastday of Peace,” address the Troubles obliquely; others, like “Stone with Potent Figure,” take on Seamus Heaney’s controversial “war poetry” in North.

McGuckian’s practice of using excerpts from biographies, cultural histories, poetry and other sources—“found” lines—is no longer a secret. These sources add yet another layer of difficulty to poems already locked within a private dreamscape. Though McGuckian generally does not reveal her sources, when she does, her work “unfolds” in ever more complex ways. “The Over Mother,” from Captain Lavender, for example, is constructed almost entirely of phrases from Diane Middlebrook’s biography of Anne Sexton and Elaine Feinstein’s Lawrence’s Women: The Intimate Life of D. H. Lawrence. Yet the poem is also about the Republican inmates McGuckian was then teaching at Belfast’s Maze Prison: “In the sealed hotel men are handled / as if they were furniture, and passion / exhausts itself at the mouth.” The title poem of Marconi’s Cottage (1991) is comprised of quotes from Anne Stevenson’s biography of Sylvia Plath. Other poems are created from biographies of Jean Cocteau and Anna Akhmatova. “I just take an assortment of words, though not exactly at random, and I fuse them. It’s like embroidery,” she has said. This method, as the McGuckian critic Shane Murphy writes, “suggests both literary theft and originality at one and the same time.”

Many of McGuckian’s intertextual sources are biographies of female artists, which suggests her shape-shifting poems present a deliberate challenge to traditional, male-authored verse. Indeed, it could not have been easy to begin writing in a Belfast scene dominated by Seamus Heaney, Michael Longley, Derek Mahon, and Paul Muldoon—though Heaney encouraged McGuckian as a student at Queen’s and remains a major influence. Like Heaney’s “Digging,” her early poem “The ‘Singer’” gestures toward a vocation but implies greater obstacles, and risks, for the female poet. The title itself evokes the tension between domesticity and poetic ambition. McGuckian’s student speaker studies at her mother’s sewing machine, “pressing my feet occasionally / up and down on the treadle / as though I were going somewhere / I had never been.” The poem ends ambiguously as the hopeful writer, watching young couples out her window, sends “the disconnected wheel / spinning madly round and round / till the empty bobbin rattled in its case.” “The ‘Singer’,” collected here, does not read like one of McGuckian’s “embroidered” poems, though the sewing imagery hints at the intertextual stitching to come.

The editors’ helpful introduction to this selection situates McGuckian’s work within familiar poststructural parameters (“playfulness, ambiguity, and flux”), but shies away from her radical intertextuality; a short footnote reads, “Medbh McGuckian typically constructs her poems out of quotations from unacknowledged sources.” The evasiveness hints at discomfort surrounding questions of authorship and authenticity. Yet McGuckian’s sources invite re-readings of her best poems, and offer a new guide to her uncharted cartographies. “I like to find a word living in a context and then pull it out of its context,” she has said. “It’s like they are growing in a garden and I pull them out of the garden and put them into my garden.” Despite such cross-fertilization, these poems are pure McGuckian. Her elusive style remains unfixed.

Published on May 31, 2016