No Obvious Distress

Amanda Quaid

reviewed by Elizabeth T. Gray Jr.

This arc of poems begins at the pivotal moment when Amanda Quaid, walking through Central Park with her three-year-old daughter, took a call from her doctor. The source of the back pain she had felt since her daughter’s birth was a tumor the size of a softball at the base of her spine: mesenchymal chondrosarcoma, an aggressive cancer so rare no one on her medical team was sure how to pronounce it correctly.

He’s talking a lot. Don’t worry

is what he somehow doesn’t sayand keeps not saying somehow, you don’t

know how he keeps on talking and keepsnot saying that. (“The Call”)

No Obvious Distress is not simply another confessional poet’s first collection, another memoir of love and loss, of major and mortal illness broken into lines on the page that will make its predictable way toward triumph or tragedy. Look at the lineation in the segment above, the deft reversals and delay. The recursive and repetitive language enacts the speaker’s bafflement at a reality no longer working as it should.

Quaid is an actor, a playwright, a filmmaker, and a dialect coach, deeply attuned to the range and nuance of language spoken and on the page. Her turn to the lyric in this moment offered an art form that can elude chronological time, that welcomes fragments and ambiguous resolutions. The lyric served as channel and constraint, a way to use her linguistic gifts in a new form. The poems were honored with literary prizes on both sides of the Atlantic.

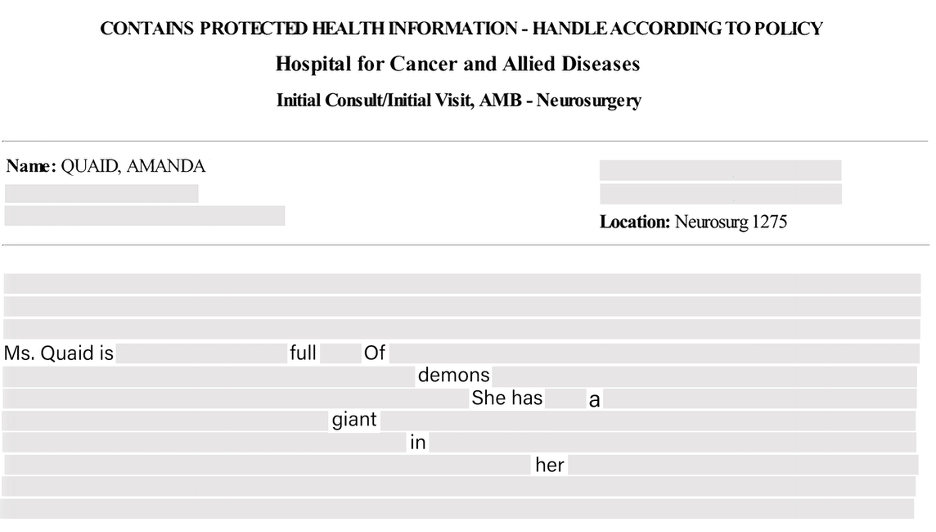

The book is divided into seven sections, each section opening with a haunting erasure poem carved from facsimiles of her medical records at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City.

The poems unfold through time, from diagnosis to treatment, toward a future that is uncertain, unimaginable, or might never be, with delicacy and strength, erudition and pragmatism, ghastliness and humor. All of those are at work in “590 Light Years Away,” as she faces three medical professionals in white coats:

It turns out the pain is a creature I’m growing. The creature

I’m growing lords over the nerves of walking,

continence, and love.These pot-bellied oracles seem pleasantly surprised I can

walk without turning in circles and that I can

feel my legs and face.Because it’s big, says the big one and I can tell

he’s a little impressed.

He leans backand rattles off a long Latin word

that translates roughly to

you’re fucked.

Other poems offer acute portraits of relationships and reactions to her cancer: husband, mother, daughter, friends, ex-lovers, possible lovers, estranged father, nurses, cardiologists, radiologists. In “How to Be a Friend to the Newly Diagnosed,” she offers:

Tell me the ways

you will harbor my child. Show me women,

arms woven like ropes, catchingmy girl as she slips from my grasp.

They also track the experience of all this through her body, which alters under the onslaught of treatment. The poems ponder what is lost, what is discovered, what is unrecognizable, what matters, what erotic means on the other side of her ordeal. In “Table by the Window,” a friend

uses that word alive like it’s not

…………..a biological

classification but rather

. a spectrum

—something one can be more of

. or less of—and… you ask yourself—have I

…………..loved enough …

widely and without

. shame …. Where

. is my

hatbox of letters

. to makea granddaughter

. blush?

The poetic forms Quaid has used to contain these intensities are wide-ranging and beautifully executed; they include the ghazal, sonnet, pantoum, sestina, anagram, haiku, haibun, free verse, and rhymed and unrhymed stanzas. Here’s a haiku from radiology:

in the MRI

I know how the woodpecker

must sound to the tree (“Haiku”)

As a poet assembles a book of poems, she or he is always faced with questions of arc, structure, arrangement, ending. Quaid comes from the world of drama and film, where playwright and director have more control over endings and resolutions. In the last sections of the book, her doctors suggest her cancer may be gone. She and her husband and child miraculously survive a hit-and-run car accident. Arrayed against this optimistic sequence of events are poems that track metastasis as a looming and organic force, cancer cells, in their Darwinian way, seeking out new territories, as her Pilgrim ancestors sought a new world bringing their deadly microbes with them. The last poem in this fine collection offers a provisional conclusion, arranging, in terse stanzas, lines culled from the erasure poems:

a young woman

is fleeting

is present

is a great Occasion.

Published on November 10, 2025