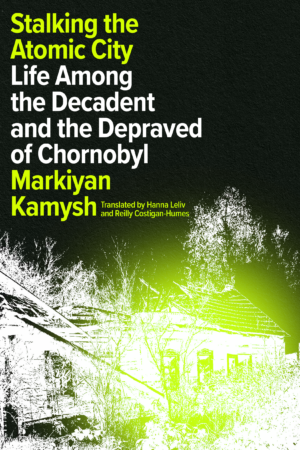

Stalking the Atomic City

by Markiyan Kamysh, translated by Hanna Leliv and Reilly Costigan-Humes

reviewed by Elizabeth T. Gray, Jr.

The disaster at the nuclear power plant at Chornobyl in April 1986 created, in real life, a geography people had only imagined. The Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant Zone of Alienation is the size of Luxembourg, a thousand square miles of marsh, ponds, forest, villages, towns, and large-scale industrial ruins, frozen in time. We’ve seen the photos of swing sets and classrooms overrun with vines, the abandoned high-rises in Pripyat. We’ve heard the stories of boar and lynx and deer and birds reclaiming their ancestral wilderness and harboring who knows what genetic mutations. The Red Forest is the most toxic place on Earth. In a hospital basement is a pile of firefighters’ uniforms that will remain deadly to the touch for centuries.

Who goes there? Engineers who monitor the fuel beneath the sarcophagus at Nuclear Power Plant Number Four. Scientists. Security personnel and local police. Disaster tourists who come for a quick visit. And, it turns out, all kinds of other people.

Markiyan Kamysh, a native of Kyiv, is a novelist and a photographer. He is also the son of a Chornobyl liquidator, one of the military and civilian personnel who worked to contain, and then mitigate, the effects of the disaster. For him, “the Zone is a place to relax.” His slender book is an introduction to the complex beyond-the-fringe ecosystem that exists in “a beautiful land of abandoned houses, canals, and agricultural machinery.” Meet the stalkers, vagabonds, hermits, scrap-metal scavengers, hippies, looters, druggies, tour guides, tourists, babushkas, police, hunters, and teenagers out for a lark. “Normal people have no business in a radioactive dump. Remember this.” The unauthorized visitors “don’t give a rat’s ass about any norms or regulations, even as the entire bottom part of the periodic table sends an electrical charge through them.”

If Hunter S. Thompson were to write a Lonely Planet Guide to the Zone, it might sound something like Stalking the Atomic City—but Kamysh’s range is broader, his perceptions and language more nuanced. The book oscillates between accounts of trips through the Zone and segments of reflection, history, and commentary. There were expeditions—solo and with others—through waist-high snow to climb Chornobyl-2, a decaying lattice of radar antennae five hundred feet high and sixteen hundred feet long, designed to detect incoming ballistic missiles, from which you can watch the sun rise. Tales of dragging an inflatable boat for miles into the Zone to sail on the lake next to the cooling tower of Plant Number Four. Of wading through leech-filled swamps, drinking metallic-flavored water, waking up next to a wolf corpse or to the sound of a mother lynx. Of thirty-day pack trips into the far reaches of the Zone, visiting villages no longer on any maps, camping upstairs in a disintegrating house, making a fire from furniture and wall paneling, and drinking vodka beside it.

Why? Because “the calm and peace that my soul needs are here.” In the abandoned village of Krasno is an old orthodox church “with a clean floor, prayer book, and a donation box. With candles, [the owl he has named] Armavir, and drowsy bees.”

Break through the bushes, stumble through the artery of an abandoned railroad that turned into a forest, into a land of wolves a long time ago. Its ties became beaches for snakes, while the paths alongside it are now tracks for wild boars. Fall down onto the gravel, take a nap in the rain, in the starlight, in the floodlight of the full moon.

And he explains:

The illegal tourists are not concerned about their own future or whatever might happen to the Zone tomorrow. We’re obsessed with the moment that’s fading away forever—year in and year out, we’ve been watching our dear Chornobyl Land crumble, the valley of our peace melt under the snow.

Come to Kamysh’s book for the ultimate insider’s tour of one of the most troubling and inaccessible places on earth. Stay for the sheer hilarity, precision, and beauty of his language. Not until the end does he answer the question I’d been asking all the way through, and then he takes it head on:

They’ll ask me, “You come here so often. Aren’t you afraid of radiation?” And I’ll tell them, “No. It’s only here that life won’t slip by me, for I’m living it in the most exotic place on Earth.” [ … ] And I firmly believe that, in two decades, I will meet those boys and girls who kept me company during my travels around the Zone in the chemotherapy room of a nice cancer clinic in Kyiv. And I know that we’ll smile at each other.

Published on November 3, 2022