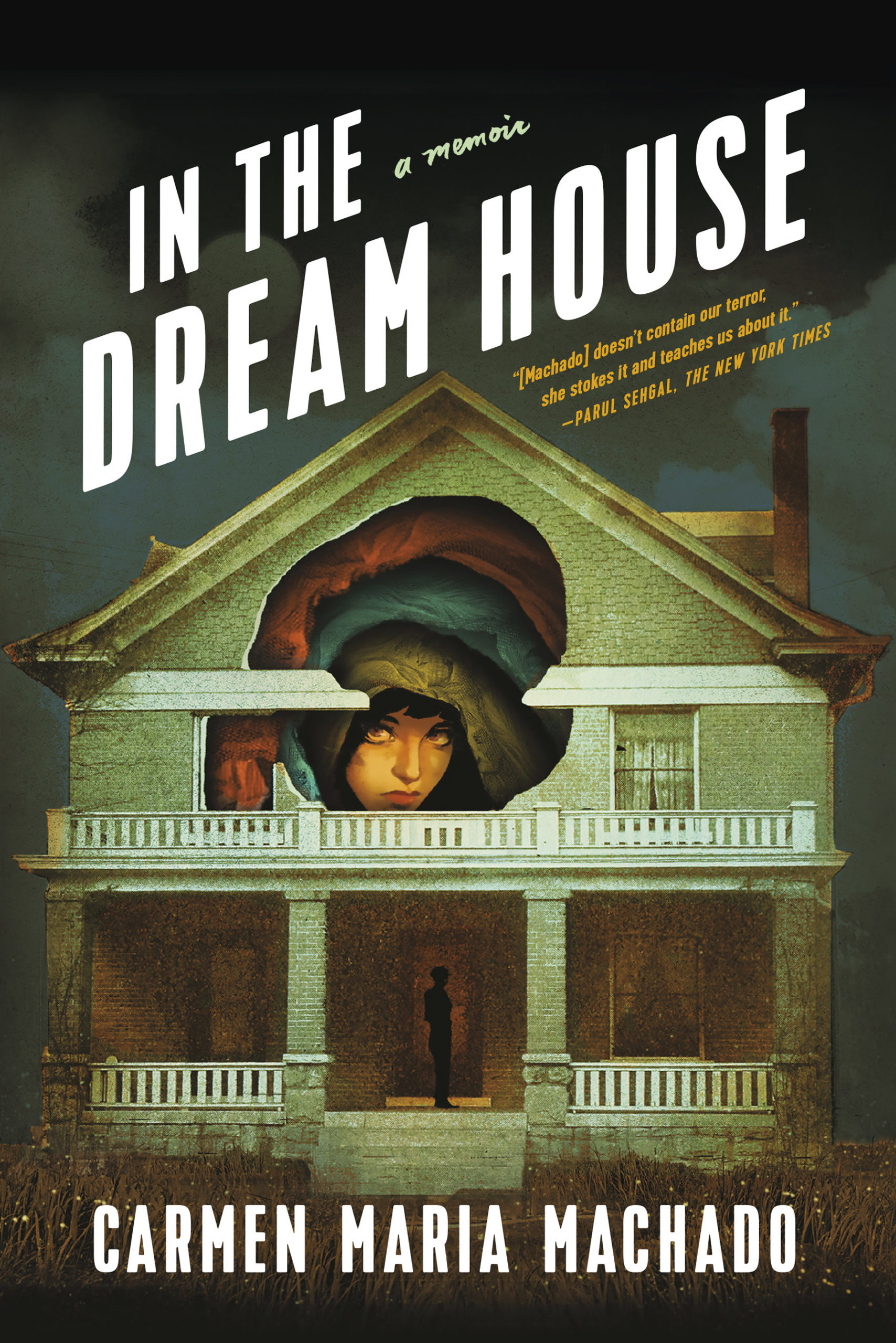

In the Dream House

by Carmen Maria Machado

reviewed by Virginia Marshall

One question is persistent throughout Carmen Maria Machado’s new memoir about an abusive same-gender relationship: How did we get here? Followed, usually, by: Is this the last straw?

Take, for example, this nightmarish moment from a fairy tale, described by Machado to show her reader the contradictory, illogical feelings she had about her then-girlfriend: the mythical Bluebeard’s young wife watches, horrified, as her new husband dances with the corpses of his former wives. Though it frightens her, this fairy-tale figure manages to convince herself that it’s completely normal. “This is how you are toughened,” Machado writes to the fairy-tale wife and to a younger version of herself. “You are being tested and you are passing the test; sweet girl, sweet self, look how good you are; look how loyal, look how loved.” That is how scary, Machado means to say, how incongruous and entrapping an abusive relationship can be.

This is how Machado reels us in. With bewitching, at times chant-like prose, Machado invites the reader into her dream house, lets us look in all the closets and the empty rooms and watch as she recreates, or resurrects—as she writes that all good memoirs should—what it was like to live for several years with an abusive partner. In the Dream House is a maze of emotion and analysis. It is Machado’s first book of nonfiction, and it complements her successful collection of short stories, Her Body and Other Parties, as both draw on fairy tale and science fiction to build full and complicated worlds for her characters.

But Machado’s memoir is not only a harrowing and enchanting journey into her past. It is also an attempt to address the absence of stories about abuse between same-gender partners. Machado lists the reasons that these stories have been silenced: fear of undermining an empowering queer movement, an overwhelming narrative of woman as abused and never as abuser, and so on. “I enter into the archive that domestic abuse between partners who share a gender identity is both possible and not uncommon,” Machado writes at the start of the book, “and that it can look something like this.”

In the Dream House spans the several years that Machado was a graduate student at the University of Iowa’s MFA program. She meets her abuser within her first few months in Iowa City, and stays in the relationship throughout the rest of her time there, even when her girlfriend moves to Bloomington, Indiana, to attend another MFA program. Most of the chapters are written in the second person; the “you” is often Machado as a younger woman. Her abuser is never named, appearing only as “she” and “your girlfriend.” The choice of the second person addressee is an important one. At times, the reader feels a part of the relationship, too, trapped with Machado in something like a fun-house prison.

Almost everything about the narrative is relentless. Machado uses a bold naming convention for each chapter title: “Dream House as…” begins nearly every section (“Dream House as Time Travel,” “Dream House as a Stranger Comes to Town,” “Dream House as Confession,” “Dream House as Dreamboat,” and so on). In “Dream House as World Building,” Machado explains this particular choice: “Places are never just places in a piece of writing. If they are, the author has failed. Setting is not inert. It is activated by point of view.” Sometimes, the Dream House is the house where she lived in Iowa City, when she met her abuser. Sometimes it is the abuser’s house in Bloomington. More often, the Dream House is a state of ecstasy, a trap, a nightmare, her regret, an escape route, or her lifeline.

In one of the most memorable and subtly-crafted chapters, “Dream House as Word Problem,” Machado describes her constant driving back and forth to Bloomington and writes herself into what seems a grade-school math problem: “If she is driving at sixty-five miles per hour, and the average length of an audiobook is ten hours, how many months will it take for her to realize she has wasted half of her MFA program driving to her girlfriend’s house to be yelled at for five days?” The problem, of course, doesn’t compute. There is no way out and no answer, and that feeling is part of the genius of this book. Later, in “Dream House as Half Credit,” Machado describes her reasons for writing the book in these short, unrelenting chapters: “When I was a child, my father told me that if I ever was struggling to answer a question on a test, I should, instead, write down everything I knew about the topic.” This is exactly what she does in so many different ways throughout the memoir, bringing in historical and cultural examples of abuse, weaving in fairy-tales about silenced women, and carefully describing her past and how it might relate to the nightmare of the present. Machado ends that chapter with this heartbreaking missive: “Let it never be said I didn’t try.”

Published on February 25, 2020