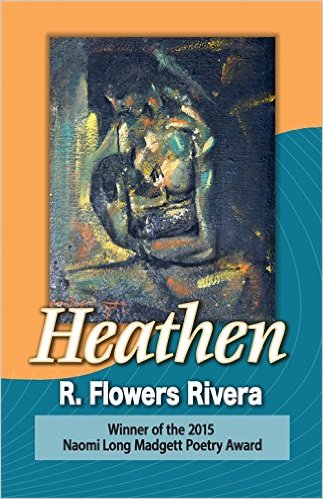

Heathen

by R. Flowers Rivera

reviewed by Elizabeth T. Gray Jr.

Heathen is a book of ferocious beauty. Its fifty-six formally varied poems explore the tensions of vision, passion, power, constraint, and pain, and do so against a backdrop of Greek myth, Christian faith, contemporary professional life, and the deep South, the taproot for much of the richness in Rivera’s first collection, Troubling Accents (2013). Appropriately, at this book’s beginning, Rivera invokes Audre Lorde and Erato, muse of erotic and lyric poetry.

The first two of the book’s four sections engage, explicitly, classical Greek myth, primarily through a sequence of persona poems. But these are not the voices of those folks you met in your Greek mythology class. Rivera has been inside these mythological figures, whose speech shifts from the formal to the vernacular, with an eye on both the divine and the human. Here is Hera, wife to philandering Zeus, at the opening of a retelling of the story of Io:

Our gin town is full of relations.

My husband and I are prominent citizens

here. The way we love each other smacks

of incest. My father and mother

were brother and sister. My husband and I

are brother and sister. Like most Southern towns,

scandals are common. People need

clear definitions of good and evil.

For the sake of convenience, I have been

assigned the latter.

(“Hera Has Her Say”)

And remember Medusa, whose hair was turned to poisonous snakes by Athena, after which people turned to stone at the sight of her? Here she is, explaining the origins of the goddess’s wrath:

I only said that we looked

about the same size. How was I to know

that an off-hand remark

would be regarded

like Friday’s catch served fresh Monday.

Okay, maybe I did kinda-sorta-perhaps

happen to have mentioned

that some of her tracks might need some more

glue. That sister/girl thing is a tenuous

business at best, but any real woman knows

her hair—today—is her

only crowning glory.

(“E True Hollywood Story: M—”)

Like Medusa’s, many of these voices reveal boldness and ambition (Salmoneus, Icarus); a passion for making (Hephaestus); fearlessness and a feral force (Persephone, not Hades); and of the constraints on, and consequences of, that force (Niobe, Promethea, Hephaestus).

In the book’s last two sections, the same goddess-grade force remains present while the speakers shift to present-day America. These poems touch on love, violence, art, racism, despair, and passion. For example, in this contemporary female speaker we might recognize Hera’s or Persephone’s power:

Put your finger on my

navel. Now wait,

close your eyes. Watch my stomach

muscle wilt, absorb my spine.Cup your sandpaper hands

along the rise of my hips.

Flesh is a lie. Hold on. Feel. I can

take you to a country I can’t pronounce.

(“I Can Show You”)

The lines are beautifully broken, their pauses and lingerings tracking breath, motion, anticipation. None of the relationships conjured in these sections is easy.

My pen is a fickle lover. She tells

such stylized lies. “This is not goodbye,just a temporary parting.” “When will you

return?” I ask. She drawssome unintelligible mark upon the page.

“That ain’t really none of your business.”Then she says, “Wait for me.”

. . .But I never let my mind

wander to whomever else’s crotch she might be holding.

I sit, transfixed by the electric white—believingshe will return. Because the day I begin to have

any doubts, I’ll have to let her go.

(“Her”)

Making her way through a web of desires and constraints toward the book’s conclusion, the fiercely intelligent speaker veers toward an uneasy but regenerative equilibrium. In the closing poem, “Here,” the speaker is turning over the earth in a garden in her suburb, in the depths of winter:

I hack and hack, attacking all that has died. This act

requires faith: that seeds have ripened and fallen,

that the roots have taken hold, that the mulch

will protect . . .Always ready for a fight,

I speak. I regard the wind, the night,

then listen for the thaw, for spring. Here.

These lines link back to the conclusion of “God Forbid: King Salmoneus,” who is consigned to hell for trying to be like Zeus:

So, here I am among the Titans,

and Tartarus looks a lot like the suburbs.

Amazingly, beneath heaven and earth,

here, in this hell, I have salvaged peace.

It’s an uneasy peace, this one, balancing in a single life the human and the divine. Heathen is a beautifully crafted and precisely configured tour de force.

Published on September 17, 2015